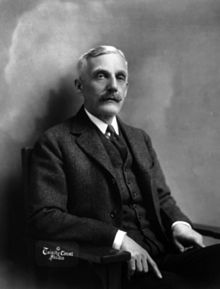

Andrew W. Mellon |

|

Mellon was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on March 24, 1855. His name is listed on the 1860 Census as "William A. Mellon." His father was Thomas Mellon, a banker and judge who was a Scots-Irish immigrant from County Tyrone, Ireland; his mother was Sarah Jane Negley Mellon. He was educated at the Western University of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pittsburgh) and left before graduating. Financial prodigy Mellon early demonstrated financial ability. In 1872 his father set him up in a lumber and coal business, which he soon turned into a profitable enterprise. He joined his father's banking firm, T. Mellon & Sons, in 1880 and two years later had ownership of the bank transferred to him. In 1889, Mellon helped organize the Union Trust Company and Union Savings Bank of Pittsburgh. He also branched into industrial activities: oil, steel, shipbuilding, and construction. Areas where Mellon's backing created giant enterprises included aluminum, industrial abrasives ("carborundum"), and coke. Mellon financed Charles Martin Hall, whose refinery grew into the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa). He became the partner of Edward Goodrich Acheson in manufacturing silicon carbide, a revolutionary abrasive, in the Carborundum Company. He created an entire industry through his help to Heinrich Koppers, inventor of coke ovens which transformed industrial waste into usable products such as coal-gas, coal-tar, and sulfur. He also became an early investor in the New York Shipbuilding Corporation. Mellon was one of the wealthiest people in the United States, the third-highest income-tax payer in the mid-1920s, behind John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford. While he served as Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Department his wealth peaked at around $300–$400 million in 1929–1930. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon was appointed Secretary of the Treasury by new President Warren G. Harding in 1921. He served for ten years and eleven months; the third-longest tenure of a Secretary of the Treasury. His service continued through the Coolidge and Hoover administrations. Along with James Wilson and James J. Davis, he is one of only three Cabinet members to serve in the same post under three consecutive Presidents. President Harding, in his inaugural address on March 4, 1921, called for a prompt and thorough revision of the tax system, an emergency tariff act, readjustment of war taxes, and creation of a federal budget system. These were policies Mellon wholeheartedly subscribed to, and his long experience as a banker qualified him to set about implementing these programs immediately. As a conservative Republican and a financier, Mellon was irritated by the manner in which the government's budget was maintained, with expenses due now and rising rapidly, with the failure of income or revenues to keep pace with those expense increases, and with the lack of savings. Mellon plan Mellon came into office with a goal of reducing the huge federal debt from World War I. To do this, he needed to increase federal receipts and decrease federal spending. He believed that if the tax rates were too high, then the people would try to avoid paying them. Mellon also believed that by reducing taxes the federal government could actually increase receipts, an idea he termed "scientific taxation." He observed that as tax rates had increased during the first part of the 20th century, investors moved to avoid the highest rates—by choosing tax-free municipal bonds, for instance. As Mellon wrote in 1924: The history of taxation shows that taxes which are inherently excessive are not paid. The high rates inevitably put pressure upon the taxpayer to withdraw his capital from productive business. If the rates were set more reasonably, taxpayers would have less incentive to avoid paying. His theory was that by lowering the tax rates across the board, he could increase the overall tax revenue. This is similar to the Laffer curve. Andrew Mellon's plan had four main points:

By 1926 65% of the income tax revenue came from incomes $300,000 and higher, when five years prior, less than 20% did. Personal life In 1900, Mellon, then 45 years old, married Nora Mary McMullen (1879–1973), a 20-year-old Englishwoman who was the daughter of Alexander P. McMullen, a major shareholder of the Guinness Brewing Co. They had two children, Ailsa, born in 1901, and Paul, born in 1907. Their marriage ended in a bitter divorce in 1912, which was granted on grounds of Nora Mellon's desertion and her adultery with Capt. George Alfred Curphey, an English soldier, and other men. Mellon did not remarry. In 1923 his former wife married Harvey Arthur Lee, a British-born antiques dealer 14 years her junior. Two years after the Lees' divorce in 1928, Nora Lee resumed the surname Mellon, at the request of her son, Paul. Philanthropy In 1913, along with his brother, Richard B. Mellon, he established a memorial for his father, the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research, as a department of the University of Pittsburgh. Today the institute is a part of Carnegie Mellon University. Mellon also served as an alumni president and trustee of the University of Pittsburgh, and made several major donations to the school, including the land on which the Cathedral of Learning and Heinz Chapel were constructed. In total it is estimated that Mellon donated over $43 million to the University of Pittsburgh. During his retirement years, as he had done in earlier years, Mellon was an active philanthropist, and gave generously of his private fortune to support art and research causes. In 1937, he donated his substantial art collection, collected at a cost of $25 million and valued at $40 million, plus $10 million for construction, to establish the National Gallery of Art on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The Gallery was authorized in 1937 by Congress. Death Mellon died on August 26, 1937, in Southampton, Long Island, New York, and was buried at Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery, Upperville, Virginia. |

|

Previous Page |

Return Home |